From Blades to Boots – Ice Skates and How They Were Advertised

Shannon Baxter

by Shannon Baxter

This is the 10th and final entry in a series of articles featuring Dartmouth’s Starr Manufacturing Company. Established as a nail factory in 1861, Starr Manufacturing soon began making its famous Starr skates and selling millions of pairs around the world from 1863 to 1939. The plant also played an important role in the sale of the first hockey sticks and excelled in other areas such as the production of the golden gates to Halifax’s Point Pleasant Park.

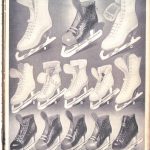

During my project on the Starr Skates here at the Dartmouth Heritage Museum, one of the most striking things I first noticed was that not all skates were attached to boots. As I began my research, this fact became obvious: Initially, skates were merely sharpened blades of metal and in even earlier cases bone. In one way or another, usually with leather straps, the blades were attached to the bottom of the skater’s boot. This was a tradition that continued well into the nineteenth century. What surprised me, however, was when I realized that even after the patenting of John Forbes’ Acme Spring Skate, Starr did not manufacture the boots to attach onto these skates. Other contemporary ice skate manufacturers of Starr were the same.

For Starr Manufacturing Company, the reasoning was simple enough. They were predominately a steel manufacturing company and not a shoe manufacturer which was a separate specialized industry. Therefore, in the early advertisements of the 1900s, and well into the early 1920s, people would find that they would have to buy their skate blades and their skating boots separately. The skates would be attached via screws that would go directly into the soles of one’s boots. All the more reason to buy a special pair of boots specifically for this purpose. The Forbes Acme Spring Skate was an exception, clamping on with its mechanism so that they could be used without ruining a pair of boots. They were clearly made with the knowledge that people would be buying footwear specifically for skating. The museum’s collection of skates has examples of various boot manufacturing companies that had Starr skates eventually attached to them. These included Samson’s Hockey Boots; McPherson’s Manufacturing in Hamilton, Ontario; W.H. Thorne & Co. Ltd. of Saint John, New Brunswick; WitchellSheill Co. Manufacturing of Detroit, Michigan, and the Thomas G. Plant Shoe Factory of ‘Queen Quality Shoes’ fame, from Boston.

By the mid-1920s, there was a sign of Starr looking to local boot manufacturers to join them in partnership. I discovered a few of the boots had Starr Manufacturing Co.’s maker’s mark stamped on the bottom of their sole. Now it is unclear where they would have gotten these boots, but it is safe to say they were likely of local make. Unfortunately, just as this trend of selling skates already attached to boots began to rise, Starr Manufacturing closed their skate production. It wouldn’t be until CCM’s skate models of the 1930s and 1940s that we finally see skates and boots joined together to be sold to eager skaters and hockey players.

To view the previous entry in Shannon’s Starr series, simply click here.